- Home

- Jimmy Sangster

Touchfeather Page 2

Touchfeather Read online

Page 2

‘He was a Captain,’ I said.

‘Among other things,’ said Mr. Blaser. ‘Among other things.’

‘What sort of things?’ I asked, not too keen to know. My memory parcel was all neatly tied and labelled and I didn’t want anyone messing about with the knots. But, before enlightening me, he shot off on a tangent which I had some difficulty in following.

‘I’ve examined your personal file very thoroughly,’ he said. ‘When you were seventeen you visited West Berlin. What was the purpose of this visit?’

That was something I knew wasn’t in my personal file, and I said so.

’Not your employer’s file, Miss Touchfeather. Mine.’

‘Why have you got a file on me?’ I said, feeling a little shirty. ‘I don’t even know you.’

‘I hope to rectify that,’ he said smoothly.

‘I’ve got to go,’ I said, getting to my feet. ‘My flight is due to be called.’

‘I’ve had you taken off the flight,’ he said.

I sat down again. I didn’t know who he was, but he just had to be someone; normally you had to lose a leg to be taken off a flight at such short notice.

‘West Berlin?’ he said.

‘I went with a school party. There were six of us taking “A” level German.’

‘Yes?’ he prompted.

‘We stayed for five days in a crummy little hotel, speaking nothing but German and visiting the museums.’

‘That’s all?’

‘What else?’ I said, still a little miffed.

‘You didn’t visit the Eastern sector, did you?’

‘Good heavens, no!’ I said. ‘What on earth for?’

He looked at me steadily for a long moment. ‘Good,’ he said. ‘I thought it must have been something like that, but we like to be sure.’

‘Sure of what?’ I asked, genuinely mystified.

But he’d finished on his tangent. He ignored my question and went straight on. ‘Your late husband was one of my couriers,’ he said.

I stared at him, blank faced. There didn’t seem to be anything to say. So Tom had been a courier; lots of Captains run errands on the side, strictly legal and aboveboard. Some deliver diplomatic pouches; others carry personal mail for overseas employees; it happens all the time.

‘It was in the course of his work for me that he was murdered,’ Mr. Blaser went on.

I remained blank faced, but only because everything had gone numb suddenly. He gave me thirty seconds to deanaesthetise before continuing. ‘I, that is my department, thought you might want to assist in the apprehension of those responsible.’ He talked like that occasionally, using long words where short ones would have been more effective. I clenched my teeth once to make sure everything was working. When I spoke, even I was surprised at how normal my voice sounded.

‘My husband died in an automobile accident,’ I said.

‘Quite,’ said Mr. Blaser. ‘But did you never wonder what caused the accident?’

Actually, I had wondered. It had been reported that he had driven into a brick wall at seventy miles an hour, just outside Rome. At the inquest a number of theories had been advanced, from the condition of the road, which was bad, through the fact that it was an unmarked dangerous bend, down to mechanical failure somewhere in the car. Accidental death had, of course, been the verdict, but the positive cause of the accident had never been clearly established. I had wondered at the time, because Tom drove a car with the same gentle care that he flew an aeroplane, or made love to a woman. Crashing into a brick wall at seventy miles an hour just didn’t fit the image. But I had been wallowing too deep in misery and self-pity to pay much attention to the coroner’s findings, and anyway I had been fifteen hundred miles away from the proceedings.

‘What caused the accident?’ I asked, not really sure that I wanted to know.

‘This,’ he said. He pulled something from his pocket and dropped it into the metal ashtray on the desk in front of him. It hit the ashtray with a solid clunk that stiffened my spine and froze me to my chair. Even from where I was sitting I could see what it was, and I just didn’t want to know. I wanted to get out of the office; I wanted to scream out loud; and I wanted to cut Mr. Blaser’s throat. But I did none of these things. With an admirable sense of the dramatic, Mr. Blaser waited for my reaction, knowing what it would be before I did myself. Hypnotised by what was in the ashtray, dreading what I was doing, but unable to help myself, I stood up, took a step towards the desk, reached down and picked up the small piece of flattened lead, feeling its rough contours between my fingers, unable to put it down, my hand shaking.

‘It’s a three-oh-three rifle bullet,’ said Mr. Blaser. ‘It was removed from your husband’s head during the postmortem.’ The little lead slug weighed a ton, but still I couldn’t put it down. Mr. Blaser continued. ‘For reasons I won’t go into at the moment, it was expedient not to bring this out at the inquest.’

Suddenly the full impact hit me; this insignificant piece of distorted metal had crashed into Tom’s skull, splattering blood and bone, extinguishing in a blinding flash everything I loved and lived for. It seemed to grow red hot suddenly and I dropped it back onto the desktop. It rolled off, onto the floor and under Mr. Blaser’s chair. He made no attempt to retrieve it.

‘Sit down, Miss Touchfeather,’ he said. I sat. ‘I’d like you to answer my question,’ he continued flatly.

‘What question?’ My mind seemed to have blanked out completely.

‘Would you be interested in helping us apprehend the man who murdered your husband?’ I still didn’t grasp what he was saying, but I must have nodded, because he suddenly got to his feet.

‘Good,’ he said. ‘Let’s go back to town.’ I got up and followed him like a trained seal.

It seemed pretty cruel at the time, but looking back on the whole thing I believe that the dramatics with the bullet were necessary. After all, I was only an ordinary sort of a girl, and it needed something pretty drastic to shake me out of the lethargy I’d dropped into. Knowing Mr. Blaser as I do now, I doubt that the bullet was, in fact, the one that killed Tom, but it served its purpose admirably. We drove to Pandam Street in absolute silence, during which time I started to boil. Slowly at first, but by the time we arrived I was willing to take on any and everything required to avenge Tom’s death.

What was required of me turned out to be considerably less than I was prepared to give. I made a contact in Rome; I identified a man I had met on one occasion with Tom; and then I enticed the man into a place and situation from which, I strongly suspect, he never emerged alive. But I didn’t know that at the time. The knowledge of what I was doing and whom I was working for came slowly, piece by piece.

Mr. Blaser never spoke to me about the first job after it was over, but he must have been satisfied because two weeks later he contacted me again, and suddenly I found myself flying with PanAm and keeping a rendezvous in Washington DC, where a dishy man, who said he was with the CIA, flew with me as a passenger on to Honolulu, handed me a small sealed package and told me to deliver it to a Japanese Colonel in Tokyo. This time, when I reported back to London, I found that I had been taken off the airline availability list and reassign. Nobody ever told me to whom I was reassign, and I don’t know to this day. That is, I know I work for Mr. Blaser, and he keeps referring to his department, but to the best of my knowledge, it has no official name, and very little official recognition. He’s got a ‘hot line’ on his desk, painted bright blue, but it is connected to I know not where. I don’t ask—and if I did, he wouldn’t tell me.

After my second job, and my transference to Mr. Blaser’s department, I was taken off flying duties for a short time and sent back to school. The school was a dignified country house, high on the South Downs, a sort of lightweight Roedean from the outside. But there the similarity ended. The curriculum was strictly St. Trinian’s for adults. I was shown how to use a gun, how to kill a man and how not to kill him, how to mix a mickey finn from the ingredients normally found in a

ny women’s handbag and how to hide things like microfilms in the most extraordinary places.

All this knowledge and a great deal more was imparted to me by a WRAC Sergeant of terrifying proportions and strong lesbian inclinations. She was rather a dear actually, and once I’d got the message across that I wasn’t interested, she didn’t bother me. She had a hatred of men that was almost pathological, and when describing the six most efficient ways to disable a member of the opposite sex, she would grow almost lyrical in her prose. Bessie was her name, and I have had cause to thank her many times for what she taught me. Her lessons have got me out of serious trouble on a number of occasions and I hope for her sake that some of the knowledge of what I have done has leaked back to her. I can imagine her beady little eyes sparkling as she reflects on the men I have left strewn in my wake. Her greatest disappointment was that I didn’t share her butch tendencies, not because she fancied me herself, but because she considered that what I possessed was far too good to throw away on any man’s altar.

I don’t agree about that, of course. To me, sex is fun—and I don’t go along with the theory about men needing it more than women either. Most women need it just as much, but they’re more capable of controlling themselves if they’re not getting it. Being a freelance air hostess has its advantages; one gets to meet a vast number of good-looking, eligible men, with the added bonus that there’s very little chance of them tripping over each other. Not being a greedy girl, I make do with three on a semipermanent basis. One of them is the airport manager in one of the South American countries; another is a Flight Captain on the New York–Los Angeles run; and my home number is just a nice guy who sells motor cars and considers a trip to the Isle of Wight as foreign travel. They’re all nice men, and I suppose I’m a little in love with all three of them. They all want to marry me to a greater or lesser degree, but I’ve had my fill of marriage for the moment and I’ve no wish to settle down yet awhile. Besides, masochistic as it may seem, I actually enjoy working for Mr. Blaser.

There are occasional drawbacks, of course, like the time I was locked in a cellar for three days with two Sicilian founder members of the Mafia, but I have learned to relegate such incidents to the realm of occupational hazards, and the drawbacks are amply compensated for by the enormous satisfaction I get occasionally over a job well done. I’m good at my job. Fortunately I don’t need Mr. Blaser to tell me this, because he never says a word. But the fact that I never seem to stop working, combined with the knowledge that I usually accomplish exactly what I’ve been asked to do, makes me secure in my self-confidence.

To put it a different way, I flatter myself I’d have made a hell of a James Bond, if it wasn’t for the fact that I’m not a fellow. As you’ll gather, I’m not modest either!

As I came into the office, Mr. Blaser was rummaging in the centre drawer of his desk. He told me to sit down without even looking up. I pulled up a chair, sat down and crossed my legs. With skirts the way they are these days, there’s not much one can do about decorum. Not that I cared much. I may be a Fred to Mr. Blaser, but a girl can’t help but keep trying. Finally he produced what he was looking for, a pipe scraper. With it he proceeded to gouge out the interior of his evil smelling pipe, sucking at the stem occasionally, making a noise like the bath water running out.

‘You’re due a few days off, Miss Touchfeather,’ he said.

‘Yes, sir.’ I was due about six weeks off as a matter of fact, but there was no point in mentioning it.

’I’m afraid I must ask you to postpone it for a few days,’ he said, blowing down the pipe stem and sending up a cloud of ash from the bowl.

‘Yes, sir,’ I said. There was no point in pressing him; he wouldn’t get to the crunch until he was good and ready.

‘Filthy weather we’re having,’ he said. I agreed we were having filthy weather, but as I had just spent two weeks in Nassau, perhaps I wasn’t as sympathetic as I might have been.

‘What do you know about Gerastan Industries?’ he shot at me suddenly.

‘Absolutely nothing,’ I said.

‘You should,’ he said, sourly. ‘They make half the instruments that keep you up in the air.’ And then I recalled vaguely having seen the name Gerastan printed on some of the dials that festooned the flight decks. ‘But no matter,’ he continued, deciding to ignore my ignorance. ‘Gerastan Industries, apart from making aircraft instruments, are leaders in the field of electronic research and development.’ I tried to look interested, no easy feat in the circumstances. ‘They are basically an American corporation with a large United Kingdom offshoot. The parent company holds United States Government contracts worth billions of dollars, mostly connected with missile development. The United Kingdom offshoot concerns itself mainly with computer development and aircraft instrumentation.

‘However...’ he said more loudly, and I jerked myself awake. ‘However, there is a small research unit in this country which has been doing some very important work. It is with this unit that we are concerned.’ He tipped himself back in his chair to an alarming angle before continuing.

‘Such is the value of the work done by this unit, that the parent company have repeatedly tried to get them to move to the United States. But the head of the unit, a Professor Partman, flatly refuses to go. He is too valuable to lose, so Gerastan have been forced to allow him to work on here in England. Two weeks ago, in Bombay, a man was fished out of the sea. He had been dead about two days. He was unidentifiable, but on him was found a microfilmed report on the work that Professor Partman’s boys are working on. There’s no need for you to know what that work is; you probably wouldn’t understand it anyway.’ Thank you very much, I thought. ‘Sufficient that the work is classified up to Maximum Red.’

Now I was impressed. Maximum Red is as maximum as you can go without climbing off the top of the scale.

‘It has been impossible to trace back the leakage, and we still have no idea as to the identity of the dead man. It is unlikely that we shall ever know. But we are reasonably sure that, since he still had the film on his person, he had not passed on any information. We think he was merely a courier, a contact man, and he died, or was killed, before he could complete his assignment.’

I thought that hereabouts I had better start contributing something. ‘If he didn’t manage to pass on his information I don’t see that there’s much to worry about. Surely it shouldn’t be too difficult to find out where the leak is at this end, and then block it.’

‘We’ve found out,’ he said.

I felt like saying that he didn’t have any problems, then. But if that was so, what was I doing there? I soon found out.

‘Professor Partman has booked a first-class reservation on Air India 102 to Bombay tomorrow,’ he said.

THREE

They call it the Maharajah Service. It’s only another aeroplane trip, but they dress it up a little. We hostesses wear saris, and we put our palms together and bow our heads instead of saying good morning. All I needed as a supplement to my permanent tan was a dark wig and a caste mark on my forehead, and I looked Indian enough to fool anyone but another Indian. My instructions were pretty flexible: I was to keep my eye on Professor Partman during the trip, and later, too, if I could work it. The fact that he was unmarried and forty-two years old made me think that there was every chance that I could work it. The trip took fourteen hours, and if I couldn’t charm him in that amount of time, then I was in the wrong job. However, if he turned out to be a misogynist or a fairy, and I was unable to keep contact after we landed, I was to report to someone in Bombay, and that would be an end of it as far as I was concerned.

Of course, my first question had been why were they letting Partman fly halfway round the world if they didn’t trust him? According to Mr. Blaser, there was no way they could stop him. It seems that Professor Partman was one of that vanishing breed, an individualist. He had even refused to sign the Official Secrets Act. If he felt like going to Bombay or Timbuctoo, there was no way of stopping hi

m, bar breaking both his legs. I must say, I built up a pretty wild picture of him from the background file that Mr. Blaser made me read. I constructed an image of a wild-eyed, shaggy-haired, scruffy extrovert, a cross between Albert Einstein and Rasputin. Nobody had seen fit to provide me with a photograph, so when a man who looked like a cross between Gregory Peck and Prince Philip took the seat allocated to Partman, I tried to turf him out. He flashed a blinding smile at me and explained in a soft, slightly burred voice that he was Professor Partman. Then he added something in what I could only assume was Hindustani. I bowed my apologies, explaining that I didn’t speak my native tongue because I was only half Indian, my father having been one of the last survivors of the British Raj, and I had been educated at Roedean. He seemed to accept this and, girding my sari, I set out to make his trip as memorable as possible. This was no hardship, because I fancied him from the moment of that first smile.

We were by no means full, so I had plenty of time to spare, and after lunch had been cleared away, I broke the rules and accepted his invitation to sit with him for a while. The Chief Steward glared at me, but he’d obviously had some sort of instruction from higher up, because it went no further than that. By the time we reached Khartoum, we were old friends and, what was more important, we had a date for dinner that evening. He told me he was staying at the Taj Hotel, which automatically became the hotel I was staying at. An hour later we had arranged to drive in from the airport together and I was beginning to think that the person who had been detailed to take over surveillance was going to earn his money the easy way.

Bill, because that’s what I was calling him now, explained that he was visiting Bombay partly for pleasure and partly because he had promised to read a couple of papers at Bombay University. He had been in India during the war, and had always promised himself he would one day return to the country that had so fascinated him.

The trouble was that about here I began to think that Mr. Blaser was barking up the wrong tree; this dishy man couldn’t possibly be what he was suspected of being. And this is where a serious flaw in my training started to show up. If I was a man, they’d say I was a sucker for a pretty face. In my case, it means that at a certain stage my emotions take over, and where I should be judging a man from the documented facts, I start judging him by my pulse rate. A quick count showed that Bill Partman was having more effect on me than I had any right to let him, and I was positively drooling at the thought of having dinner with him. I said he was a dish. Well, it went deeper than that. It was painfully obvious after the first hour that he reminded me too much of my husband to be healthy. I’ve met all sorts of men in all sorts of situations, but the deadly ones, as far as I am concerned, are the big, gentle-eyed, soft-spoken men with large capable hands, and a way of looking at you as though you are the only other person who exists. They have other characteristics, these men, but they are too subtle and too personal to put into words. I’ve only met three of them. I married the first; I made a complete idiot of myself over the second, who was already married; and Bill Partman was the third. I hoped that Mr. Blaser and his informants were hopelessly wrong and, if they weren’t, wondered whether or not there was anything I could do to lessen the ultimate fate that would befall Bill Partman. Of course, there wasn’t, so I clung desperately to my first hope, that the whole thing was a ghastly mistake.

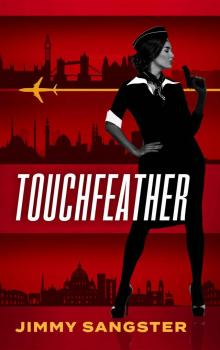

Touchfeather

Touchfeather